Why learning is central to city futures - A policy briefing from PASCAL International Observatory

Over half of the world’s population now live in cities, and cities account for by the largest share of GDP. Cities are recognised as the drivers of national and regional economies, and ensuring the resilience of cities in the face of the current economic downturn and the pressures of globalisation is a necessity for national governments and city and regional leaders as they strive to ensure competitive advantage, secure their place on the world stage and the prosperity and well-being of their communities.

Cities can face a broad range of challenges including rapid urbanisation, migration from rural areas, environmental issues, growing social inequality, and loss of community and identity, as well as demands for efficient and effective governance and smart delivery of public services arising from tight or reducing resources. Typically strategies for city development emphasise a number of specific aspects, most often focussed on:

- Infra-structure development, including connectivity and international links;

- Access to finance and investment;

- Encouraging growth of hi-tech industries, productivity, knowledge and innovation;

- Sustainability and smart technologies;

- Promotion of a vibrant culture emphasising a strong sense of place.

Taken together these are usually held to be the factors to attract and retain talent and investment and sustain economic development. Policy actions are developed for each of these, including improving transportation, aligning public sector spend to encourage investment in high-value economic sectors, skills development strategies, improving knowledge transfer, to be delivered through suitable partnerships and co-ordinating structures between public authorities, business and civic agencies.

It is also increasingly recognised that economic development will only be sustained if it is accompanied by social and cultural development to sustain the city both as an attractive place for people to live and build a fulfilling lifestyle, and as a place which allows continual adaptation to new opportunities as technologies and demand change. Studies of city resilience show that it is those places with integrated communities, high social capital and strong identities which recover faster than those lacking social cohesion. Cities which create processes to sustain conditions for socially inclusive continuous learning and innovation are the best placed to succeed. It is these processes which define the learning city, and which place-based policies for economic development cannot ignore.

The idea of the learning city

The recognition of a close relationship between learning and place is not new, and can be traced back to ancient Greece. Its modern re-emergence since the latter part of the 20th century has drawn upon changing notions of learning which go beyond the traditional distinction between initial education and continuing education and embrace the concepts of lifelong learning and learning throughout life. Varied opportunities for learning are important, not only at school, but also in work and business, public services, and social and cultural life, to allow adaptation to emerging technologies, and economic and social innovation. Education and learning are at the centre of strategies and policies for economic development and improvement of the environment and well-being of communities. A learning city can be characterised as one in which communities attempt to learn collectively to change their own futures. It is of crucial importance to understand how, through appropriate strategies and policies of public governance and intervention, this notion can be given reality.

What is meant by ‘learning’ in this context?

Here ‘learning’ refers to a broad concept which includes, but goes beyond formal education services. It includes not just knowledge and skills (human capital), but also less formal and informal learning through networks (social capital), and the capacity to use learning to adapt and adopt innovations to meet emerging economic opportunities, to maximise the quality of life in communities, to improve city governance, and foster civic participation. It therefore includes not only individual learning but also organisational learning, and the translation of this learning into innovative practices and products.

Some cities have styled themselves smart cities, sustainable cities, healthy cities, cities of culture, science cities, and cities of ideas. Such initiatives are often led by particular specialists, be they technologists, environmentalists, public health professionals or the creative industries. Some are now adopting a broader strategy prompted by the PASCAL EcCoWell concept. Successful delivery of any of these strategies depends on mutual shared learning. A learning city is one which embraces learning, not only at the individual level, but also across organisations and in government.

Key tasks for the future city

Arguably, there are 4 main tasks for the successful city of the future. It will need to:

- Stimulate the city economy through improving jobs and skills;

- Provide an appropriate range of public services, including neighbourhood management, available equally to all;

- Provide physical and environmental care, ensuring confidence to existing and potential residents;

- Facilitate a strong voice for residents and influence over local conditions.

It is the contention here that learning, in different forms, is vital to each of these.

What is the contribution of learning in different aspects of city development?

There is a growing body of research which highlights the contribution of learning, in different ways, and at different levels, to sustaining successful city economic and community development (for a recent international review see Osborne et al, 2013).

Learning and economic performance

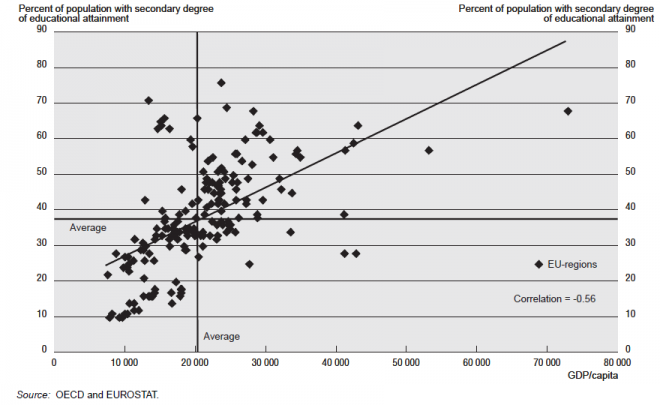

Human capital, (that is, the stock of skills and qualifications in a population) far more than physical infrastructure, explains which cities succeed (Glaser, 2011). He claims that in the US, a 10% increase in the proportion of the population with a college degree is associated with a 22% rise in gross metropolitan product. The OECD (2001) has demonstrated strong correlations between the level of qualifications in city populations and indicators of city economic performance. The graph below shows the relationship between the proportion of population with secondary education qualifications and regional GDP for EU regions. The strength of this relationship at national level has been demonstrated again recently in the first reports from PIAAC (OECD, 2013).

In some regions the strongest impact on economic performance comes from the influence of tertiary education, whilst in many others, the strongest relationship is with attainment in secondary education. What is clear is that the impact is mediated through regional organisational structures and institutions: it is essential that there is a ‘good fit’ between the forms of educational outputs and the characteristics of the region and its industrial base.

Organisational learning and innovation

However, it is not individual learning per se that matters for regional performance but the use made of individual skills in business and governmental organisations through organisational learning which creates growth. There is a good case for strong co-ordination between local employers and individual learning. Innovation by firms is the cornerstone of regional growth. One way of illustrating this is through the relationship between ‘patent intensity’ and regional GDP. The graph below, from the OECD (2001) clearly shows a strong relationship.

Research suggests that ‘learning-by-doing’ and ‘learning-by-interacting’ within the workplace may be more important than initial education in influencing the likelihood of successful innovation in organisations. The provision of learning networks, innovation hubs and clusters can only assist this process. Willingness by government agencies to explore and adopt innovative approaches to public service provision likewise can facilitate efficient and effective processes and provision to support adaptation to emerging needs.

Learning and the citizen: the wider social benefits of learning

At the personal level, research has also demonstrated clear links between learning and a range of aspects of social behaviour (Feinstein et al 2008). Amongst the more striking examples are in relation to health, crime, tolerance and civic participation.

People with higher educational attainment tend to have healthier lifestyles, and be fitter and slimmer. They are less likely to be smokers, likely to take more exercise, and have increased life expectancy. There is evidence that these benefits can be passed on to the next generation. Those with higher education qualifications are not only the most economically productive, but also most likely to engage in a range of social networks.

Keeping people in education is associated with decreased rates of crime. It has been estimated that in the UK and increase of 16% in people educated to degree level would save £1bn in crime related expenditure. People with no qualification are more likely to be persistent offenders, whilst those with higher education qualifications are generally these least likely to commit crime.

Even a relatively short period of participation in adult education, especially by those from disadvantaged initial education backgrounds, can have beneficial effects, contributing to positive changes in behaviours and attitudes. For example participants are likely to be more socially tolerant and show less racism, be more likely to engage in civic participation and voting, show healthier lifestyles and make fewer demands on health services.

Men with the poorest literacy and numeracy skills tend to lead a solitary life, and be less likely to be parents by their mid-thirties. Women with the same low skills are also less likely to have a partner, but more likely to be parents and to have large families.

Social capital and social cohesion

Just as learning can have strong individual benefits, research also suggests that the distribution of educational opportunities can, in certain contexts, have a strong influence on social cohesion. Whilst the relationship is complex, learning can promote social cohesion and strengthen citizenship through deepening social networks, developing shared norms and values of tolerance, understanding and trust.

Moreover, increased learning is associated with greater likelihood of employment, and reduction of poverty and income inequality. Attention is increasingly drawn to the importance of learning opportunities for older people (see Schuller and Watson 2009), to sustain them as active, contributing members of society through continuing employment and active social participation.

Learning and community development

Communities are important as the places in which people live their lives and shape both the perception and reality of public policy and services. While community participation is not a new idea, the forms in which this can be pursued have been transformed in recent years by advances in technology, there is increasing evidence to support the contention that local-level co-operation builds stronger communities, which in turn create possibilities for effective solutions to complex problems. These possibilities are most likely to be realised through building both community capacity and the means by which actions can be turned into effective policy and provision. Information, connectivity and learning are central to these processes, both within communities and government agencies.

Strong communities, high on social capital, enjoy a wide range of benefits too, ranging from better physical and mental health, higher educational attainment, better employment outcomes, lower crime rates, and an increased resilience in face of threats and interventions.

Putting learning at the centre of place-based policy

This paper then, has reviewed the role of learning in the making and re-making of places. The role is extensive and complex, but not often explicitly acknowledged in policy for the development of regions, cities and towns, and local communities. It is time to put that right and recognise that learning, broadly defined, is a key concept in supporting, sustaining and joining up policies in a coherent framework for city development.

Local economies are not made by city leaders alone. What they can do is create the conditions and the structures to position their city to be best placed to take advantage of local assets and adapt to future change, working closely with business, schools, colleges and universities, workforces, and local communities. As economies become less and less ‘natural resource’ based and more and more ‘knowledge-based’ it is essential to invest in human resource development through well designed adaptive systems for learning and workforce development.

Successful businesses are adaptive businesses. Successful communities are adaptive communities. Adaptive communities must be learning communities keeping abreast of change.

Learning cities will be the truly smart cities in the quest for sustainable economic prosperity and social well-being.

References and further reading

Campbell, Tim (2012): Beyond Smart Cities: How Cities Network, Learn and Innovate, London, Routledge

Feinstein L, Budge D, Vorhaus J and Duckworth K (2008): The social and personal benefits of learning: A summary of key research findings, London: Institute of Education

Glaeser, Edward (2011): Triumph of the City: How Urban Spaces Make Us Human, London, MacMillan

OECD (2001): Cities and Regions in the New Learning Economy: Paris: OECD

Michael Osborne, Kate Sankey and Bruce Wilson (eds) (2007): Social Capital, Lifelong Learning and the Management of Place, London: Routledge

Michael Osborne, Peter Kearns and Jin Yang (eds) (2013): Learning Cities: Developing Inclusive, Prosperous and Sustainable Urban Communities, International Review of Education vol 59 no 4

Norman Longworth and Michael Osborne (eds) (2010): Perspectives on Learning Cities and Regions (PASCAL), Leicester: NIACE

Rogers R and Power A (2000): Cities for a Small Country, London: Faber and Faber

Tom Schuller and David Watson (2009): Learning Through Life : Inquiry into the Future for Lifelong Learning (IFLL), Leicester, NIACE

JET/January 2014

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login to post comments

- 133 reads